You Can Stop Making Practice Apps Now

Stop guessing-and-checking kids into oblivion. Start teaching them.

As a learning science engineer, I have an ask of developers in the edtech space:

Stop designing practice apps and start designing instructional apps.

What’s the difference? Let me show you.

Imagine I’ve made a new app. Don’t worry, I’ve run the placement tests and verified that you have the prerequisite skills. It’s time to teach you something new, something you do not know. If you knew it, you wouldn’t be in this app.

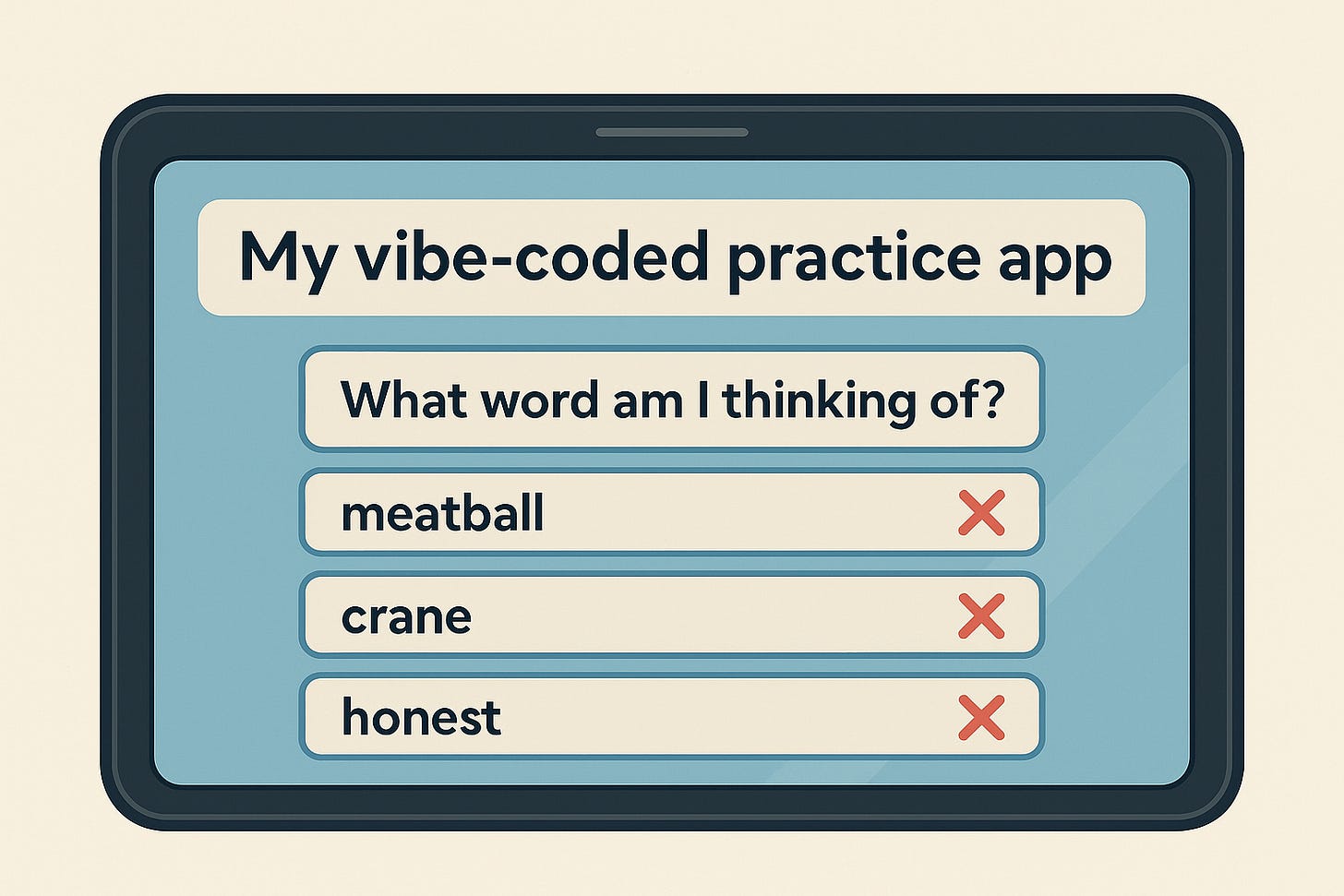

Here’s the first learning task you see on your screen:

“It’s time to play Guess The Answer. Type your answer in the box.”

You guess.

You’re wrong. The answer was sausage roll.

Next task.

“New problem. Type your answer in the box.”

Wrong again. It was petunia.

x20.

Clearly nobody would think this is good, nor that filling a child’s day full of these exercises would help them learn powerful knowledge about the world around them. But too often, this is pretty much what lands on my desk when a team excitedly shows me their prototype for a new educational app.

Developers are good at finding the essential content to teach. They know how to add points and badges and make things look pretty. They’ll even sometimes read about cognitive load theory and make sure there are only three things on the screen at once.

And after all that—just another freaking practice app!

Demotivating and Inefficient

Hey kid, here’s a series of multiple-choice question for which you’ve never seen a model.

Sorry, you got it wrong.

Hey kid, here’s a game to learn super important stuff! You’ll love the controls. 3, 2, 1. Go!

Wrong. You’re wrong. Wrong again. Start over. You’re still wrong.

Hey kid, welcome to the base of Moron Mountain. After you practice this wrong, then you go up a level to practice another thing wrong, then one day you’ll be at the top!

Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.

This design isn’t just demotivating for the child—though that part is critical. Every app developer needs to bake into their motivation model the fact that early success is an incredibly powerful motivator to get kids to attempt increasingly hard things.

The design is also wildly inefficient. This is “Trial-and-error”, “Guess and check.” “Hope and pray” learning. Run around like a rat in Skinner’s maze until the correction sequence forces you into discovering the underlying pattern. Make like a chimp in the infinite monkey theorem: with infinite time on a typewriter, they’ll eventually type Romeo and Juliet. Eventually.

There are better ways to teach.

Those of us in learning science design are tired of rejecting what begins as a thoughtful concept but ultimately reveals itself to be nothing more than a low-success test of material the learner hasn’t ever been taught.

Why do developers make this mistake?

I think it boils down to two major reasons.

The first reason is that many simply don’t understand what the science of learning implies for the sequencing of tasks. Instruction needs to proceed in a highly controlled way—from acquisition learning to fluency building, to generalization, application, and maintenance. So many apps fail outright because they skip the acquisition phase that is heavy on models, examples, and advance organizers and just give kids unguided practice tasks. This doesn’t work.

Most practice apps could easily be repurposed into fluency-building apps, but we already have an abundance of those! There are tons of math-fact drilling apps and plenty of vocabulary flashcard and quizzing apps. We don’t need more of them. These projects will be rejected because we are trying to bring effective instruction—not trial-and-error practice—to the masses.

The second reason developers might make this mistake is that instructional apps are way harder to design than practice apps. They require carefully designed videos, worked examples, and diagrams. They need to proceed from a full model (Whole) to a series of partial or faded models (Parts) to having the student do the whole thing independently (Whole). This “gradual release” is one of the component shifts of Direct Instruction.

This means the developer must labor over splitting up their app into many more discrete segments, attend to the brisk alternation between models and “checking for understanding” questions, and make important decisions around how to remove supports as students gain expertise. It is simply easier to dump a question bank into an app and say: Give them a bunch of these, and if they’re right, green checkmark; if they’re wrong, show them autogenerated feedback. (Which the student inevitably skips. More on that in another post.)

What to do instead?

If you want to be ahead of everyone else in the field, start thinking about how your practice app is actually just the last phase of the “Whole-Part-Whole” or “gradual release” sequence. An instructional app generally proceeds from 1. A full demonstration of the skill (here’s how you tie your shoe), then goes to 2. Partial models that require more and more from the student (e.g., student ties the first part, the tutor ties the rest), and ends up at 3. the student repeatedly doing the whole thing by themselves (Look at you! Now tie your shoes 10 times and you can play a shoe tying game that will make sure you never forget it).

And if you really want to blow my mind, your instructional app will teach it to me so well, the first time, that I skip off into the sunset with a smile on my face.